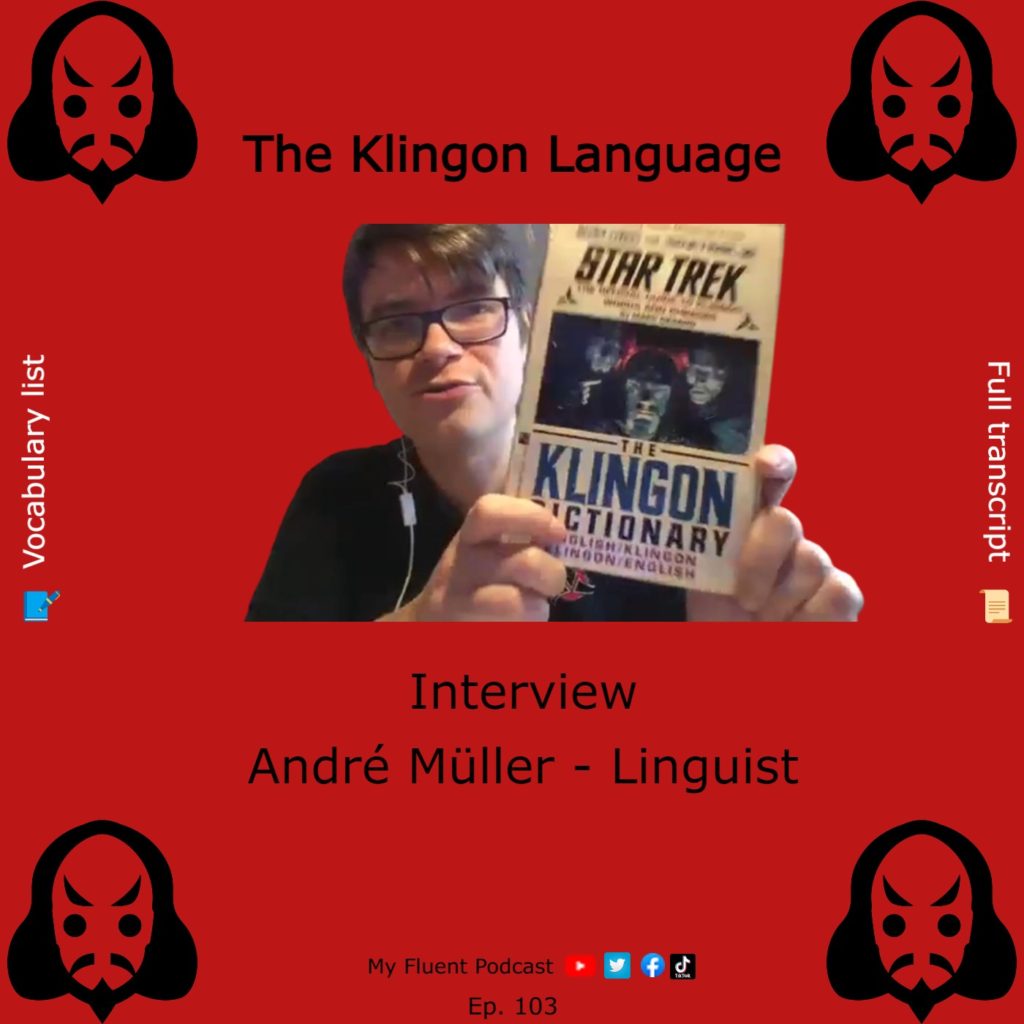

Ep. 103 shall inspire you and show that it’s possible to become fluent in a constructed language (conlang). André Müller, linguist and polyglot learned to speak Klingon. He even taught Klingon. He talks about his passion and shares his insights on how to learn Klingon. We also touch on some other linguistic topics, for example his PhD mission in Myanmar.

Links

The best place to start learning Klingon:

Klingon language – Wikipedia gives you a good overview on the Klingon language.

The Klingon Dictionary: The Official Guide to Klingon Words and Phrases (Star Trek)

Vocabulary list

To Pick up: Pick up a language, to pick up an accent.

Right away: immediately

PhD: PhD is short for Doctor of Philosophy. This is an academic or professional degree that, in most countries, qualifies the degree holder to teach their chosen subject at university level or to work in a specialized position in their chosen field.

Let’s get off the ground: to begin to operate or proceed in a successful way. (I did a mistake there and said “to” instead of “off”

The Klingons: The Klingons are a fictional species in the science fiction franchise Star Trek.

A Linguist: has two meaning: a person skilled in foreign languages. a person who studies linguistics.

For brevity. “I left it out for brevity”: because of shortness of time.

A phoneme: a speech sound in a language

Pocket money: a small amount of money given to a child by their parents, typically on a regular basis.

If I hadn’t met Klingon, I wouldn’t have studies: If I hadn’t passed the test, I wouldn’t have had/wouldn’t have the opportunity to… | WordReference Forums

An agglutinative language: you have a root of a word, and then you add suffixes little endings one after another, like for example in Turkish, in Hungarian and Finnish.

The causative: to cause someone to do something (a suffix or a function that you can apply to a verb)

A geek: an unfashionable or socially inept person.

A nerd: a foolish or contemptible person who lacks social skills or is boringly studious.

To derive words from other languages: have (a specified word, usually of another language) as a root or origin. “the word ‘punch’ derives from the Hindustani ‘pancha’”

Your feedback on this episode

Leave us a voice recording/video or text in which you share your opinion with us. By clicking on the Reply button you will be able to choose between the 3 opions to give feedback. Thanks a lot!

Transcript

André: Hi,

Daniel: Hello, André (Andrew), how are you doing?

André: I’m fine thanks. Nice to see you.

Daniel: It’s nice to see you too. Unfortunately, I can’t say “hello” in Klingon, because I had to learn from you that there is no such word in Klingon.

André: Yeah, that’s correct. Klingons just start right away talking about whatever they want to say. They don’t waste their time greeting people.

Daniel: Because yesterday I stumbled upon your crash course. Your Klingon crash course.

André: Ah, on YouTube?

Daniel: Yes, exactly. And that’s why I could pick up some information, it is really interesting. Yeah.

André: Yeah. Thanks.

Daniel: Thank you for being here and taking the time. I’m going to introduce myself. I am Daniel, as you know, I come from Switzerland from the German speaking part.

My project is pretty simple. I started out podcasting in English in order to improve my speaking skills because I get no practice at all. And that’s my method: I interview people and at the same time I can share my experience and of course the experience of the experts and I try to inspire other people.

So that they can get fluent in what language it may be (in whatever language). Right. But my focus is on English. I would say let’s begin or do you have any questions?

André: Oh, I think we can, we can start right away.

Daniel: Okay, perfect. So would you please introduce yourself?

André: In English or in Klingon? No, better in English. Okay. So my name is André Müller. I’m originally from Germany. I was born in Leipzig and now I live in Leipzig again, but I’ve spent around eight years or seven and a half years in Switzerland in Zurich where I did my PhD in linguistics and well, after that I came back to Leipzig. I’m not only a linguist. I’m also – I would say – a polyglot because I love learning languages. And even though I’m not fluent in all of my languages, I just really love learning new languages. And among them are several languages of Southeast Asia or Asia in general. Because that’s one of my main interests, but also artificial languages.

So I speak Esperanto and I speak Klingon Yeah.

Daniel: Nice. And we will learn more at the end of this episode, because first we would like to focus on Klingon. Let’s get to the ground. So what is Klingon?

What is Klingon?

André: Klingon is an artificial language that was created by a linguist for the movies and the series of Star Trek. So, you know, Star Trek, that’s a very famous science fiction series, from the U S and it’s been started in the 1960s and it’s been going on and especially this year, there are so many new seasons of shows that are already on TV or available online. And so there’s a group of aliens called the Klingons. In the beginning, there used to be the bad guys, but with relationship with Federation, with us improved and so now they are not really the bad guys, so yeah.

And yeah, and the studio said that let’s make a realistic language for them. So they hired the linguist from the U S Marc Okrand and he invented Klingon as a language with vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and he invents new words every year and increases the language. And it’s actually used and learned by several fans of not only fans of Star Trek, fans of constructed languages.

So yeah, I’m one of them I speak Klingon

Daniel: Nice. And I think that, or let’s say I first thought that it was Scotty from the series who invented the language. But, but then I learned that I was not right. So maybe you could explain more about that?

André: Actually, you are right. And I left it out for brevity, but, it’s true that for the first Star Trek movie. They said okay, let’s have the Klingons on speak in Klingon and then they didn’t hire anyone. But the actor who played Scotty in Star Trek, James Doohan. He said, yeah, oh, let’s just write down some words that they can say.

And so he just came up with words that sounded exotic to him. So words that have a lot of *Klingon sounds*…

Daniel: yeah.

André: …inside and he wrote down like eight words or eight lines that (or seven) that we can hear in the first movie, but they didn’t have any meaning assigned to them. So just some words that the Klingon commander can say to his crewmates.

And then for the third movie in, I think it was 1984 or five, Marc Okrand was hired and he used those seven or eight words and said, okay, Well, at this point, they say *Klingon sound*, so *Klingon sound*should be a phoneme, a speech sound in that language. And then he created the grammar and more vocabulary. I was for that. So he, so Marc Okrand invented the language, but one could say James Doohan gave it a little start and invented the first few words.

Daniel: Okay. Yeah, that sounds really interesting. So my question now was what inspired you to learn Klingon, but it is obvious, right? It’s because of the series.

André: Yeah. And you’re right. I think it started in 1996 or so when I was still in school and I watched Star Trek which was on TV at the time still is, but yeah, and I was a big fan of Star Trek and of course I heard a little bit of spoken Klingon on in the series and I thought, wow, cool.

*in Klingon* interesting words. but then I saw in the bookshop that they had the Klingon dictionary out and you can actually buy it and learn the language. So I bought it for my pocket money. I bought the German version because that was in Germany but I can also show the English version of the book, the Klingon dictionary.

Yeah. So you can actually, it’s not only a dictionary. It also has the basic grammar insight and you can learn all about it. And so I started in 1996 to go through the book and, oh yeah. And also I should say I was always interested in languages. So, maybe in 1996, I don’t know. I didn’t speak a lot of languages aside just like German and.

English from school. And I think I knew a little bit of like the Greek alphabet and the Cyrillic alphabet and the Arabic alphabet, but languages in general were interesting to me. So I felt like, wow. Language from Star Trek. I have to try to learn this, but then only later, much later in 2003 or four or so, I picked up the book again and thought like, wait, I now know more about languages and now I can actually understand what he wrote. And then I started to really learn it.

Daniel: That is really nice. And so can we say that Klingon in a way showed you the direction to the linguistics field?

André: Yeah, it sort of did. So I would not say that if I hadn’t met Klingon that, I wouldn’t have studied linguistics, but, many things about languages I understood through Klingon actually because Klingon isn’t an agglutinative language. That means that you have a root of a word, and then you add suffixes little endings, one after another, like Turkish, like Hungarian Finnish.

They, they work in similar ways and this was something new to me. I used to know German and English and a little French and maybe a bit of Chinese as well, but I felt like, wow, you can actually add words. It’s like playing with Legos. And, yeah. Also some things like the so-called causative that may maybe, you know this from some languages it’s a suffix or a function that you can apply to a verb to make.

It means to cause someone to do something like if you have the word to eat and you add the suffix or you change the verb a little bit, and it means to cause someone to eat, which usually means to feed, you know, and I didn’t know that this was possible because I was young. And then I saw, oh, this is how this is interesting.

And then I saw, wow, this is actually quite common in the languages of the world. Many languages have that.

How do people react when they get to know that you speak Klingon?

Daniel: And how do people react when they get to know for the first time that you are fluent in Klingon?

André: Ah, some laugh some find it really funny because either they find it cool because they know I already know a lot of languages and then I also know Klingon well or because they know I’m a Star Trek fan. So they think, well, okay, he’s really a geek or a nerd, even though it’s Klingon.

Yeah. Some people think that, wow, that’s a waste of time. That’s so meaningless. Why don’t you learn another language, a real language? And then I say, well, I already know a couple of real languages. And, then I explain to them that, yeah, okay, real languages are useful and necessary. And it’s good to learn them, of course.

But then they are hobbies and. I think even learning an artificial language like Esperanto or Klingon as a hobby, just for fun, just because I enjoy talking to people in Klingon or having a blog in Klingon or something or in Esperanto, that can give me joy. I enjoy that. It’s like other people playing the guitar or playing chess.

Yeah, Exactly. They don’t usually want to play in the band and become famous or win the chess championships. They just want to enjoy themselves. And, yeah, for me that’s Klingon and Esperanto and some other natural languages too.

Daniel: It’s a hobby. And I mean, we don’t juge others when they say I like going to the cinema. It’s a hobby and that’s it. Right. And, we have joy in doing such things.

André: Exactly. Yeah.

Daniel: Is Klingon based on an existing language

André: really.

Daniel: Is it truly constructed?

André: I would say it’s truly constructed. So the inventor, Marc Okrand plans to make the language as different from English as possible so that it’s not like, you know, he could, he could have said like, well, this word is that word. This word is that word. And the grammar is just like English, but he wanted it to be really credible and different from languages from earth.

So he also included some points that are really rare in the languages of the world. Like the combination of sounds that exists, you know, usually language is, the sound system of language is very regular and you have like, if *K T P*, and then you have the voiced sounds *G D B* and so on but nothing Klingon. In Klingon you have P and T, but you don’t have a K sound.

You have a *Klingon sound*sound instead, and you don’t have *B D G* you have “B”, but the *D* is pronounced different it’s *Klingon sound*and the “G”doesn’t exist, but it has. *Klingon sound “RR”* so on. So, he didn’t base it on natural language.

Daniel: I see.

André: Of course, if you look at it, all the features you can find in Klingon, almost all of them, are also found in natural languages, but you find them in Greenlandic and this feature you find in Swahili and that feature you find in Chinese.

So , it’s a mix.

Daniel: Okay. And you told us before something like the new words, right? So, I mean, what happens when new words come up in Klingon? So is it always Marc Okrand who decides that it goes to the dictionary to the official dictionary, right?

André: That’s actually exactly the case. Every year there are two meetings. Well, during Corona times it’s difficult. So these meetings are online, but usually they happen one meeting, it’s the heavens in the U S and the other one is the type home. It happens in Saarbrücken in Germany. And Marc Okrand is usually present and he reveals new words.

And this is always, everyone is so happy and looking forward to the new words. And so he comes up with these words and he gives an explanation, sometimes some example sentences, and it’s really him who invents the word. So if I think, ah, damn, I don’t have a word for, I don’t know a word for cardboard or a word for peanut.

So I cannot just say, oh, well let’s say, it’s not all the word *in Klingon* or something because, I am not an authority in the sense that I can make up words so I could ask Marc Okrand. I could say, I have this translation project. I really need a word for cardboard. Can you make one up? And then maybe if I’m lucky, you will get back to me and say, ah, yeah, that’s the word?

Daniel: That sounds complicated. Right? He’s like the king or the guru.

André: Yeah. Yeah. It’s a bit like that.

Daniel: and how can we think of the gathering? I mean, I am seeing this picture right now before my eyes, a bunch of followers dressed as a Klingon going to this gathering or how does it work?

André: Yeah, a few people who dress up as Klingons with clean on foreheads, their forehead and, um,Klingon swords the backlit, the famous, clean

and sore.

Daniel: cool.

André: Yeah, but I would say these are the minority of the people who attend those gatherings, maybe 10% or 15% or so, most of the people are like dressed normally or maybe, maybe they wear a Klingon t-shirt or something.

But, yeah, but it’s always mixed. Some people are not really that much interested in the language, but they love the gatherings and the, they like, they enjoy being there and hearing a little bit about Klingon. Some people are eager to learn the language and they go there and some people already know the language quite well, and they go there to speak it, to practice it and to maybe learn a little bit more about the language.

Yeah.

Daniel: and actually how many people in the world speak?

André: That’s very difficult to say. It also depends on what it means to speak Klingon, like, there are people who are really fluent who know all the words and they’re like around 5,000 words. I would say the people who know all the words and can speak it fluently, maybe 20, 30, 40, and people who can really converse in Klingon. I would count myself in that group. I can speak it almost fluently, but sometimes I struggle and sometimes I have to think about words or I mix up a prefix or something. That could be. 50, 60, 70, 60, maybe 60, but this is just a guess. And then there are, of course, people who know a little bit of Klingon the, they do the course on Duolingo and they, maybe they have the book and are reading this and practice a little bit.

Maybe that’s 200 people who can hold a small conversation include

Daniel: Okay. And compared to other languages such as Esperanto, or let’s say French, how difficult is it?

André: How difficult is it? I would say, it’s not that difficult. It’s actually easier than most natural languages, including French. I would say. Because Klingon is very regular. The grammar is, as I said, quite exotic, or let’s say not like European languages, but it’s very regular. So if you learn a rule, it usually applies to the whole language.

You can use it all the time. There are a few exceptions, but you can manage them. It’s like, oh, okay, well, this rule works for everything, but not these three verbs or something like that. The difficulty is that you cannot derive the words from other languages that you know. So when I learned French or Russian, or I don’t know, then I at least can think, oh yeah, this word I know there’s English as the same word or a similar word.

It’s an international word, Esperanto is easy because we Europeans know all the words already, basically. And the grammar is also very regular for Klingon grammar is regular, but it’d be different. But the words I have to learn, like for example, the word for water is *Klingon word*. I can’t derive that from “Acqua”, “Wasser” “or “not English” or something

Daniel: How would you say I drink water?

André: *Speaking in Klingon*.

Daniel: Okay. Yeah. That

André: So

Daniel: sounds funny

André: big what’s that look is I drink it. And then you already noticed that, the object comes first and then comes to the verb with. Klingon has an object, verb, subject word auto. So it’s the inverse of the usual English word order.

Daniel: I see. I see. And what about the peculiarities? So are there maybe some peculiarities that come to mind in the language?

André: Yeah, sometimes.

Daniel: What do I mean by that? For example, I learned from a book, there is this indigenious tribe of Brazil called Piraha. And for example, they don’t use words for color. It doesn’t exist.

They always use a word like blood for a red thing, for example. And what is even more strange to me is that they don’t use any number words. This is really strange to me.

André: Yeah. Yeah. Sometimes people ask me, can you explain how Klingon work? And then I explain a little bit, and a few features are really strange or unusual. I would say, one of them is that, Klingon does not have gender, so it’s not masculine, feminine neutral words but that’s normal in the world, but it has something similar.

So when you, when you put the plural ending on the word, you have to decide between three plural endings and they depend. On if the word is, a thing, if it’s a person or if it’s a body part. So, if you say the plural of a thing, for example, a park is a book and, books is puck may, so there’s may as the ending.

Um, if you describe people, so Klingon is a Klingon. If you say Klingons several Klingons, it’s not cling on may, but clean and pool because it’s a person capable of speech. So you have a different ending. And then for body parts, um, for example, um, um, men, men is the, I mean, uh, mean dupe is, uh, eyes. So you don’t say men may or men, but men do. And, um, yeah, that’s, that’s quite rare in the languages of the world that you have a noun class for body parts only.

Daniel: What could be an explanation for that? That there is a specific thing for body parts.

André: Yeah, so good question. So Marc Orkland never explained why this is the case in the language, but of course we can, we can assume. And we can imagine maybe it’s because, body parts usually come in, in two, you have two eyes, two arms, even Klingons have two arms. They have other things that are twice.

So they have two hearts. They have two stomachs, I guess, two livers and other things. Um, and, um, so maybe originally. In Klingon, thousands of years, thousands of years ago, maybe this do ending was something like the Juul, like in, in some languages that have a dual, like, I think Arabic has it or used to have it.

Where, when you have two things, you have a different kind of plural. Just for two, maybe that’s the origin.

Daniel: Okay. I see. Well, I wanted to ask you where should learners begin with their journey in Klingon? I mean, you mentioned before Duolingo, you mentioned the dictionary and what would you recommend? Where should we start?

André: Um, I think, um, as a, as a very first start, I actually would recommend just the Wikipedia article on Klingon because it’s quite large, it’s quite complete and it gives a good explanation so people can get an overview how Klingon in general works. I think that’s always a good start to start with the Wikipedia article too, to know a little bit about the language.

And then I always recommend the Klingon dictionary. Mine is pretty used, it’s already falling apart. So this is a very good idea because it starts explaining the grammar and it has the most basic words. As I said before Duolingo is also a good start, but sometimes I think that, the words are you learn them in a strange order.

I think. Among the first words you learn is the word for a sense or a sensor like to scan a scanning device. And I think that this should not be among the first five lessons. This would come later, maybe first learned water and speak, eat diet and so on. But it’s a good start and good practice because it lets you translate sentences.

And then a very good place is the Facebook group “Learn Klingon”. You can ask a lot of things. There are lots of experts there who can answer your questions. You can try writing a small sentence or speak a book a day and other people can correct you if you like. There’s also a group on Discord.

So, it’s called the Klingon language Institute Group, I think, and you can join there and meet a fellow Klingon on this. And that’s also where we have a lot of online meetings. What else is there? I used to teach Klingon in Switzerland, actually. So.

Daniel: That is so cool.

André: Yeah. And since you are in Switzerland, maybe, yeah. That’s interesting for you too, it was a few years ago that a famous, adult learning center, the so-called “Klubschule Migros” asked me if I wanted to teach Klingon. And I said, why not? Usually they offer languages like French, Spanish, Russian, Arabic, and so on. But yeah. Then I taught Klingon for three years and actually, now they asked me, even though I’m living in Leipzig again, they asked me if I wanted to teach Klingon remotely via zoom or something.

So, maybe this year, if I’m lucky and enough people sign up, I can teach Klingon in, in German.

Daniel: This will be so cool. So let me know if you will start the online lesson, then I can put it on my show notes as well. So what was the typical learner like when you were in Switzerland giving lessons. Were there always only fans of the Star Trek series or were there other people as well?

André: Mostly there were fans, mostly Star Trek fans. I also, at the beginning of the courses, I always ask like, okay, can you introduce yourself? And also say, what brought you to the course to Klingon? Most of them were Star Trek fans, somewhere like science-fiction fans in general. Some people were just very interested in artificial languages.

We also had one mathematician, I think a lecturer from the ETH university in mathematics. And he said like, okay, here, he likes Star Trek, but most of all, he likes systematic structures. So he wanted to see if Klingon has a systematic structure and patterns.

Daniel: Okay. And what was his conclusion

André: Um,

Daniel: the end?

André: I think I,

Daniel: has it structure enough for him?

André: I think, I think he did, I guess he thought, well, okay. Yes. This is a very structured language. You asked a lot of questions about mathematical expressions, how to say the square root of seven in Klingon. And I said like, um, I don’t know. I have to look at that, but I never, I never used this.

Daniel: Okay. So from your explanations, I assume that the community is very supportive, right? So if I were to begin to learn Klingon there. would have enough people there to help me write and converse or to, I mean, because a huge partof languages is also the speaking part. And I imagine it’s difficult to pronounce correctly.

If it’s a constructed language,

André: Yeah, that’s right. You’re right. So for the pronunciation, I can also recommend YouTube videos. You could search for a Klingon teacher and you will find videos that explain the pronunciation, but, you’re absolutely right that the big part of language learning and for me also, the fun part is actually speaking with people and that does work in Klingon, but, usually there are so few Klingon speakers that it’s difficult to find them in the wild.

And that’s where the internet is very useful. So in this Facebook group and in the discord group, there are many people who are eager to speak and practice with you. And also to explain the grammar with you and to you. And, um, yeah, so there’s a good way to start and practice. And I also enjoyed that yesterday evening, we had a group meeting online on discord and one guy was explaining the names of animals in Klingon.

So I learned a few new words for animals in Klingon and we used the language. We talked about animals in Klingon.

Daniel: Yeah. Cool.

André: Hmm.

Daniel: So now let’s talk about identity a little bit, because in my opinion, identity plays a huge role when learning a language, for example, also the culture, the food, and whatsoever. So since Klingon is a constructed language. What do you say about that? I mean , is there enough culture or do you know what I mean?

because it’s all like made up.

André: Yeah, I know like you can, you can totally immerse yourself in Chinese culture,

history and the language, but for artificial languages, it’s sometimes a bit more difficult. For S parental people say that as Esperanto has a culture. And I would also agree with that because the meetings and the community of Esperanto speakers is so much bigger and so much older that there has developed.

Sort of culture with Klingon speakers. I would hesitate to say that this is the case also because some of them try to follow the Klingon thinking from the series and say, yeah, I’m a warrior. I’m strong and powerful. I do not cry. If I make a mistake, that’s not a problem. And others are more like, I’m not a Klingon I’m a, I’m a Terran, I’m human.

I just want to learn this language. And they are interested in Klingon culture, but they don’t subscribe to this. I also like as a learner or former learner of Chinese, I don’t necessarily want to be Chinese. I don’t want to drink hot water. And, and yeah, I dunno practice,

Daniel: Yeah.

André: Chinese belief systems are so, but I’m interested in the culture and want to learn a lot about it.

So, yeah.

Daniel: And I remember that from the series, sometimes the Klingons are eating something, which is terrible. Humans would never eat that, so,

André: Some humans do eat worms or bugs, but yeah, I would not. I have to say like no bugs or insects or worms for me,

Daniel: You must not take my question seriously. And of course, I mean, culture, you have science fiction, right? You have all the series and any, and you have in a way you have something to share when you are speaking the Klingon language. Of course.

Solet’s speak maybe of Star Trek Discovery, in particular season one, which came out 2017 because this series is very, very Klingon heavy in my view.

And also when it comes to listening . to Klingon because they are speaking aloud in Klingon. So my question to you is, is there a difference of the Klingon language compared to maybe all their series or all the movies? What can you say about that?

André: Yeah, there is a little difference. I would say maybe you could say there are three different kinds ofKlingon in the Star Trek series. One is the Klingon you hear in the movies and the older movies, like Star Trek, one to Star Trek, seven or six, and let’s start at six. Which is very good because Marc Okrand made up all the dialogues and made up new words and wrote the lines.

So this is a very good clean on, and it’s very interesting to hear that. Then there is the Klingon we hear in The Next Generation, deep space 9, Voyager and Enterprise, which is. Yeah, which is Klingon, but it’s not good Klingon. I have to say because the makers of these series did not consult with Marc Okrand.

They just looked up words in the book and the actors mispronounced them. The grammar is all muddled up and it doesn’t make any sense. Sometimes it’s very difficult to really even understand what they are saying. In Voyager, for example, I remember there was one episode with Alanna Torres, who I can’t remember what she did, but I think she remembered or in a vision, encountered her mother on the barge of the dead or something like that.

And there was a Klingon sentence said, and it was impossible to understand because the grammar was wrong. The pronunciation was. Terrible, but, but then for the discovery, they actually did not hire Marc Orkland, but they hired a very fluent and very good clean on speaker, from Canada, Robin Stewart and also known, with her by her single name cov.

And, she made all the dialogues and, uh, if she needed a new word, she asked Marc Orkland to give her that word.

Daniel: Yeah. Sorry to interrupt you André do, do you have a Klingon name too?

André: I don’t have a Klingon name. I sometimes, yeah, sometimes try to come up with one, but then I’m, I don’t know. I’m too picky with names. So I just see myself as a Federation, Xenolinguist who explores the Klingon language.

So I’m just Andre or sometimes Andrew.

Daniel: And on discovery series one, I think they, they even hired an accent coach to train the actors. And for me, it just, it blew me away because it was so authentic, even though it’s a constructed language, but it was, it was amazing. So I recommend all of the listeners to watch, especially season one, to listen to the Klingon language.

André: Yeah. And especially you can hear, they get better with the, maybe in the first episode, it’s still a bit choppy, but then it gets better. And especially the two actors were really great. One is I can’t remember her name, but the actor of L’Rell and also the actor of Voq and they have a really expert pronunciation.

Mary was her name. I remember that.

Daniel: Yeah. And I assume that this was really hard work right. With the accent coach, because you, you have to train yourself to get used to pronouncing correctly. And I mean, with you too André, because you began 1995, I think you mentioned it right with the dictionary

André: 95 or six. Yeah.

Daniel: And up to this day. So you had many years and still you don’t even consider yourself as a hundred percent fluent.

André: Yeah. That’s because I, in the beginning I dabbled with the language a little bit, but I didn’t have any guide except for this book. And so, I made a lot of mistakes, beginners mistakes, and nobody corrected them. But then in 2000, 2 3, 4 or something. I became a member of the online community and I saw what other people wrote.

I asked questions, I was corrected and I felt like, wow, I really have to rethink everything. Recently I cleaned up, papers, old papers from years ago here in my apartment. And I found the old Klingon notes from, I don’t know from 2002 or three. And they were full of mistakes, not just like mistakes, like, oh, I used the wrong word, but like, God, what did I do to the grammar?

What was I thinking? Yeah. I think last year or two, two years ago , when Corona, I, started relearning the Klingon language, like, like fully, I said like, okay encounter a word that I don’t know yet. I will put it into on Anki. That’s the vocabulary program that I use.

I will put it into Anki and repeated. So everyday I repeat the Klingon words. So I try to remember them. And I think that’s how I know, like around 2,500 words now. So not the full lexicon, maybe half of it, but the useful health of it, I would say

Daniel: Okay. And can you imagine creating or constructing a language on your own.

André: I can imagine that. And I tried it before. I tried it twice because I thought, wow, other people invent languages. Maybe I should try that. Maybe it’s interesting. And like, I started a bit, but then I gave up because, it’s, it’s very, it feels very arbitrary. I think I’m not a very creative person in the sense that I can come up with the language that I like, because I always think of, ah, I like this and that language I want, like I like this feature so much.

I want this language to have this feature, but then I think like, where do I take the words from? I mean, what is the word for word in the language that I’m inventing? I can’t just pull it out of thin air. I want to take it from somewhere else and maybe change it. So one idea is that I have for the far future, for creating one construct language, so you know, Latin and, you know, like French Italian, Spanish romance language is all derived from Latin, Latin in the times of the Roman empire had system languages that were spoken in Italy systems languages, like, like Sabelic and Faliscan and Oscan. And Umbrian like languages similar to Latin, like telling the similar to French, but they went all extinct and only let them survive. And I wonder what would have happened to French Italian Spanish, if not Latin had so wife, but

Boskin

Daniel: Yeah.

André: then, and then I, what I want to do is like to learn Oscan or Umbrian or one of those, and then apply all the same sound changes that led from Latin to French lessons to Spanish, to Oscan or Umbrian to see how those languages would sound today.

Daniel: That would

André: is like,

Daniel: amazing, but are there enough sources you can, draw on

André: I think that might not be enough sources. So there are a few sources and we have inscriptions in these languages, but I think the vocabulary, if we collect all the words, I think it’s only a few hundred words for those languages, so might be difficult, but it’s an interesting thought experiment of all of history.

Daniel: Do you have a favorite saying in Klingon?

André: Yeah, I thought about it. And I have two sayings that I really like if I may mention two sayings.

Daniel: Yes, of course.

André: Yeah. So one of them is *in Klingon* which literally means, sometimes everyone encounters Tribbles, Tribble is a small fluffy creature in Star Trek, and Klingons really hate them. So the sentence actually means something like, sometimes everyone has bad days and I like this because this is a sentence that can apply to Klingons and the warrior culture, but also to us humans on earth.

And the other one is *in Klingon* When we are together in a greater whole, in a greater entity, we can succeed. So this is also something that is typically Klingon like, as a group, we can conquer everything, but it’s also applicable to the normal world. And so to us on earth, like if we struggle, if we work together, we can maybe achieve what we plan.

Daniel: And where did you get them? Are there from the series or did you pick them in a book?

André: As far as I know. So, I have them in, on key in my vocabulary learning deck because they are useful. But I think originally they were published in a book called the Klingon way also by Marc Orkland, where he collects, or collected, typical klingon sayings and idioms and wise words. And, you know, those are two words that are found in that book.

I believe.

Daniel: I find it beautiful also that Marc created this language without even imagining that one day people would speak that language to this. So. Cool.

André: Yeah, exactly. He was really surprised when he learned that people have actually learned the whole book and are trying to converse in the language in the nineties or late eighties. Yeah.

Daniel: Yeah. And are there other constructed languages that you understand?

André: So I’m fluent even more fluent than in Klingon in Esperanto, which is an international auxiliary language. So it’s supposed to be easy to learn and easy to use. And there are maybe a few hundred thousand speakers in the world who speak Esperanto. And I learned that in 2002. Yeah, 20 years ago. And, I have used it quite, quite often in my life and like to go to, Esperanto meetings.

I have friends to speak in Esperanto. I use it online. Yeah. And another language, a small language where I know that I know only like, a bit of is Toki Pona. That’s I think I have a book somewhere here. Yeah. Talkie Pona. It’s a very simple and easy language, with only 125 words.

And you might be surprised that the, yeah, the dictionary is quite fat, but um, all the words you have to combine them. So there’s a word for house and the words, there’s a word for water, but if you say toilets, you have to combine these words and say a Waterhouse tail or NASA or something.

Daniel: that sounds also very interesting. And I don’t know if you like to talk about a YouTube video, which you made for. I can’t pronounce it.

André: Wouter Corduwener, Yeah, I remember.

Daniel: A Dutch YouTuber and the title was Xenolinguist speaks Klingon and many other rare languages. And I was impressed because you were speaking in 18 languages and this was some sort of a bet every time that Wouter would not understand you or, or not able to respond, he would pay you five euros.

And I think in the end, he paid you about 50 euros, I think. And this was so incredible. I will read it very quickly so that the languages were English, German, Esperanto, Mandarin, Thai, Dutch and Burmese. Jinghpaw, Klingon, Spanish, French, Russian, Tsez, Shan, Latin, Toki Pona ,Ido, Dene, but I can’t even pronounce some of them.

I’m sorry!

André: one of them. No problem. One of them was pronounced Jinghpaw

Daniel: Okay.

André: it’s a language Myanmar. I also have to say like, um, so who is watching this video or listening to this podcast will now think like, does he really speak 18 languages? And I have to say, I don’t really speak 18 languages, but Wouter asked me to like toot to say stuff in all the languages.

I know, even if I know only a little bit of them, so it would not be enough to know. Hello, thank you. In, I dunno, obey.

Um,

Daniel: Sure. But you are too humble because I saw that too, that you made a comment after the video was uploaded in which you explained that you are not really a hundred percent fluent in every of these languages.

And I just thought you are just too humble and beating yourself up too much because

It’s really impressive what you are capable of. It’s just beautiful. I must say.

André: Yeah. Many of these languages I do not practice anymore very much so. For example, I used to know Russian. I think I still can hold a conversation in Russian, but I don’t learn it anymore. So I’m gradually forgetting all the words and I’m only working on like seven languages or so I’m really working on and I hope that I can maintain them and the rest, I think like, thanks.

I remember a little bit, that’s enough for me.

Is it easier for linguists to learn languages?

Daniel: so would you say as a linguist, is it easier to learn language?

André: Yeah, I would say so. Not because of some strange talent or so, but it’s easier because as linguists, it’s an easy thing to just read a grammar, like a grammar designed for linguists, and then remember how the grammar actually works. So for many language learners, it seems dry and they can’t remember this, or they have a hard time understanding maybe what the causative is or something.

But for me as a linguist, this is like, oh, this is the causative of the language. Okay. All right. I know what this means. Oh, I learned to just ** and something other people have to really focus. What does this mean for me? It’s already a familiar thing. So the theory helps me to put this into practice.

I would say.

Daniel: Yeah, that makes sense. And a very difficult question. Now, what does it require to be a good linguist? Maybe it’s difficult because there are many different types of linguists, I guess.

André: Yeah, that’s difficult to answer. You’re right. There are many different kinds of linguists, some linguists work a lot with numbers and with statistics or programming and they have statistical models and AI or computer learning algorithms and so on. So this is very useful and I think it’s encouraged nowadays that linguists know a lot about statistics and about programming.

Daniel: Yeah.

André: But they also should know a lot about languages, not necessarily a lot of languages. It’s very useful to have a wide view about what is out there, not in, not necessarily in languages but also in the research, what other linguists do and what theories are out there. So you can maybe take their theories and apply them to your focus area or something like that.

Yeah. I’m not sure.

Daniel: You did your research in Myanmar. So what was the mission about?

André: Yeah. My focus there was to explore the language contact in the north of the country. Myanmar or Burma because in the north of the country, there’s a state called the ?Kachin? State. There are lots of small indigenous languages they’re being spoken and a lot of people speak more than one language.

so these languages influence each other in different ways. And I try to find out how they influenced each other. Like not only that they exchanged words, long words, but also the grammar influenced each other. And you could say, oh yeah, this feature must have come from that language. And I try to look into that.

So I did not do a lot with numbers or statistics or these things, but more qualitative studies, like not quantitative, but qualitative looking at what is out there and trying to explain this.

Daniel: But did you have to learn all of these different languages up to a certain degree?

André: Luckily not all of them. I had to learn Burmese the national language of Myanmar, a tool to be able to speak to people and to get around there. Of course. And I also decided to learn Jinghpaw, which is the lingua franca in the north, the language that most of the people there speak. And I have to say learning Jinghpaw was easier than learning Burmese.

But the other languages, I did not learn fully to way that I could speak them, but I learned them a bit. I learned how that grammar works. That’s for me, that’s something that’s easier to remember. But I did not learn all the words for all these, I don’t know, 10 languages out there. But since some of them are very similar to each other, it helped me so that, sometimes I could understand bits and pieces of these languages, but there’s a linguist. You don’t always have to learn the languages fully. You can analyze them with the help of native speakers and without the above dictionaries and grammars.

Daniel: So it was not always field work. For example, talking with the people, right there.

André: Yeah, exactly. It wasn’t always that sometimes it was, but oftentimes it was, that I went there with an assistant who spoke, Jinghpaw Burmese and English and, we used all three languages to speak to each other and then she helped me to find the other people. And then we transcribed what they said.

So I recorded people and I had them give me the translation of what they said either in Burmese or in Jinghpaw or sometimes in English or Chinese even. And then at home, in Switzerland back then I try to figure out how the language works by comparing the original and the translation

Daniel: Sounds very interesting.

André: Yeah.

It was,

Daniel: May I ask you what your next mission will be? Your maybe it’s not a mission, but your, upcoming plans.

André: I don’t know yet, so I have finished my PhD. I moved back to Germany and now. Well, taking a break from my PhD and I am also looking for something new to do. I don’t know what that will be. I might not do anything in research maybe.

Daniel: Constructing a language. Of course.

André: Oh yeah, yeah. Learning, , learning Umbrian or Oscan maybe, maybe.

Yeah. But, so I recently like basically, last week I got asked if I could work for the university of Zurich again, but remotely from my computer and to, work in a new project called out of Asia that will compare the languages of Asia or Eurasia with the languages of the Americas because we know America was settled by people from Asia who went over the Bering Strait to north American and south America and linguists want to find out if there are shared words and also especially shared grammar between those two continents.

And they asked me if I would like to work on noun classes in those languages. So I might go through a lot of language grammars and take out information and put them in the database. But that’s only a small job that I will do for the next six months, I think.

Daniel: I see.

André: And after that something with languages, but perhaps not a post doc, I will see.

Daniel: Okay. Thank you

André: I tell you, I take offers. I take offers.

Daniel: Yes. The last question will be about deepL or machine learning programs. So do you think these types of softwares or websites are a good tool to learn languages?

André: Hmm. Good question. I don’t know. DeepL very much. I know it’s said to be better than Google translate and I have sometimes compared to translations in both. And of course I noticed that over the past years Google translate came much better. When I sometimes have to read articles in Japanese and I don’t speak Japanese, I can put them in Google translate and the outcome is actually good enough for me to understand what the article is about in deepL I have not tried this.

But is it good for language learning? I think sometimes it is, but I only use those for looking up collocations. So for example, when I talk to someone or chat with someone in Spanish and I don’t know if you say, like I, I dream about something. Do I dream about off with, or how do you say that?

I think in Spanish, it’s something I dream about with you or something. If I don’t know this, I can enter it in Google translate and usually the result will be very good because it’s a collocation. A bunch of words that occur there frequently, so that’s useful, but I would not use it to look up single words because words have a lot of translations.

I would use a dictionary for that, but of course, if I come across something that I cannot understand in Russian or Spanish or Chinese, then I can put it into Google translate or deep L and hope that this will help me, but I would not use it as a main tool for language learning.

Daniel: Yeah, sure. That makes sense. So thank you very much, Andre. It was really interesting to hear all of these interesting tips and tricks and the story behind a Klingon. And I wanted to ask if it’s okay. If I share the link to the Klingon crash course in my show notes,

André: sure. No problem.

I think I also gave a crash course on Navi which is another constructed language

Daniel: oh, great.

André: which I used to learn a little bit and used to speak a little bit, but not anymore.

Daniel: So I also wanted to ask you if you were up to it, maybe, maybe in three months, four months, I don’t know, to make another interview about Esperanto. This would be so awesome.

André: I would love to do that. Sure.

Daniel: Okay. So thank you very much. And I will have a very good time when I add the podcast because I love to relisten to it and then to let it sink.

Right. And, it was really a pleasure to have you here.

André: Yeah. So at the end, I want to say to you, but,*in Klingon* *still in Klingon**and still 🙂 * *in Klingon* uh,

Daniel: Great. And what did it mean?

André: It means I want to thank you very much that I could be here and talk to you and talk about the Klingon language

Daniel: It was a pleasure. Thank you so much, André

André: Also to me, thanks . Yeah. See you Daniel .

Daniel: no, no, sorry. Sorry. I have a last question. I forgot. This is really important but you don’t have to take it too seriously, right?

you are able to speak 18, 19 languages and you were in Switzerland, but you are not able to speak the Swiss dialect.

André: That’s that sort of, right. I, it depends on how much wine I drink, but I didn’t fully learn Swiss German or Zurich German, but I could understand, I can understand everything. I’m not sure how it is with a Wallis dialect.

Daniel: yeah.

André: uh, generic.

Daniel: Does

André: yeah, but whenever I try to speak Swiss German, sometimes some Swiss people tell me that, oh, that sounds already quite good. And other people say, oh God, no don’t please. Don’t horrible. Oh I got a bit disencouraged and thought like, it’s fine. I speak standard German.

Daniel: because there are so many different, um,dialects, so it’s very difficult for you to pick

up and

And you don’t, you don’t need to pick up, it’s not necessary.

André: yeah. Andin our institute in Switzerland, everyone was from somewhere else. One person was from Zurich. Other people were from Basel , but Bosley from Bern, from Berner Oberland.

Daniel: Mm.

André: I don’t know Aargau, and whenever I asked, like, how do you say this in Swiss German, blah, blah, blah. And they were like, depends. It depends on God.

Everything depends. So in the end I didn’t learn anything

Daniel: Okay.

André: embarrassing.

Hmm.

Daniel: Awesome. No, don’t take it too seriously. I was just joking.

André: no, it’s fine. It’s fine.

Daniel: Okay. Bye

André: Okay then. Bye.

Daniel: Yes.

More Klingon stuff

Did you like this episode?

Then you might also like episode 101 – Lingo Junkie. How Eugeniu from Moldava became a US citizen and fluent in English.

1 Trackback or Pingback